by Jessa Alston O’Conner

As Yellow Signal exhibitions continue across Vancouver over the next several months, it is worth exploring more about the origins for this city-wide project that date back 15 years. In 1998, Jiangnan: Modern and Contemporary Art from South of the Yanzi River was a major exhibition series across Vancouver on a scale not before seen outside of China. In his talk at Centre A in March, curator Zheng Shengtian spoke about origins of Jiangnan and how that series opened doors for Yellow Signal today.

Zheng explains in his curator’s talk that in 1997, Hank Bull (co-founder of Centre A) travelled to China where he visited Shanghai and other cities in the Yangzi River delta region, also known as Jiangnan. Returning to Vancouver with great enthusiasm, he began to generate community interest in bringing Chinese art to Vancouver with a desire to introduce these artists and their works to new audiences. Meetings were held, but no one dreamed that it would grow to become city-wide, but also one of the biggest exhibition projects ever undertaken in the greater Vancouver area.

Jiangnan began in 1998 at the Vancouver Art Gallery with Pan Tianshou’s first exhibition ever in North America. 12 other exhibitions followed, in almost every venue in Vancouver including non-profit centers like Western Front, Access Gallery the Contemporary Art Gallery, Artspeak, Grunt Gallery, Presentation House, and also in private galleries. It was a major series of exhibitions that brought more than 24 Chinese artists to Vancouver. Jiangnan came to a close with a symposium that included major scholars from around world.

The Chinese name for the Yangzi River is Chiang Jiang, ‘the Great River’. Jiangnan means “South of the River” and is a region that includes Hangzhou, Suzhou and Nanjing, and the metropolis of Shanghai.

This area is lush, supplying food, silk, tea and ceramics to northern China. At times, it was the location of the nation’s capitals, and during end of the Northern Song Dynasty in 1127, it was home to many of the scholars and artists of China. With the Republican Revolution and the end of Qin Dynasty in 1911, the role of art changed with the time. Instead of serving elite and Imperial interests, the art schools that opened in Shanghai and Hangzhou were more openly accessible, and modern artists from these regions began to study not only traditional art forms, but also Western and international media and art trends, including the avant garde. Yet under General Mao, Social Realism was adopted as the only officially accepted artistic style. This curtailing of artistic self-determination ended with his death in 1976 and by the 1980s, the region once again rose as a prominent creative center in China.

China is diverse country, and Jiangnan has been a center of artistic production since at least the Southern Song Dynasty (1127-1279). Some artists continue in traditional practices of painting, and others breaking from it, re inventing tradition with new media. Jiangnan sought to reflect this diversity of artists and perspectives. Some of the artists selected were part of the artistic community that were exiled from China after the catastrophe at Tiananmen in 1989, and other artists were practicing within China. After the artistic style of Social Realism being the sole genre enforced for so many decades, the artistic exploration of personal, self-expression and abstraction became a highly politicized act. The works in Jiangnan demonstrated how contemporary artists in China were not only working in the transitional period in the late 90s, but also in a time when transnational networks of economy, culture, crime and communication were interconnected. Jiangnan was about artistic concerns that mattered globally, not just to artists in China. Some artists drew from traditional Chinese art forms and themes, while others created works that stemmed from universal experiences devoid of Chinese signifiers, relating to global audiences.

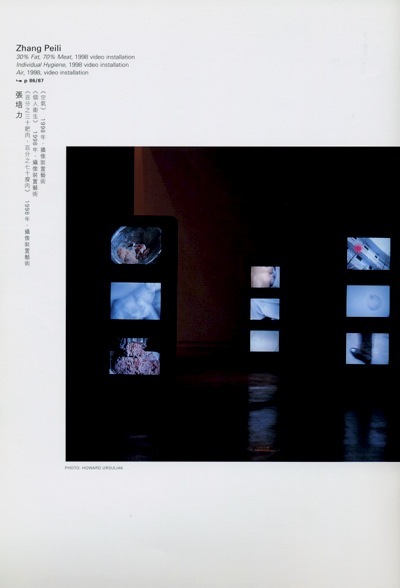

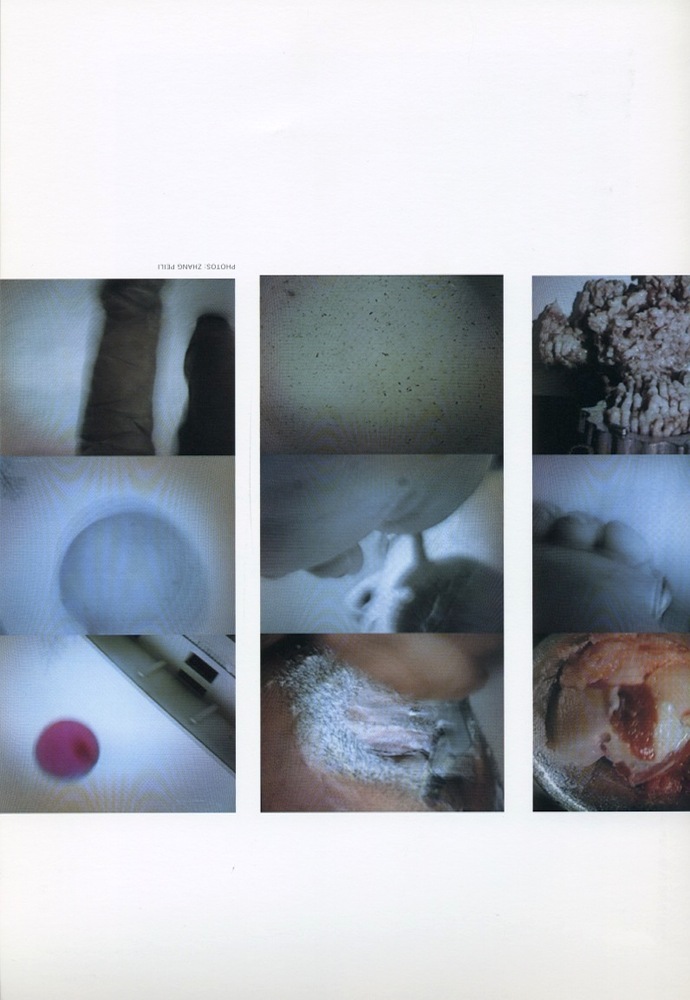

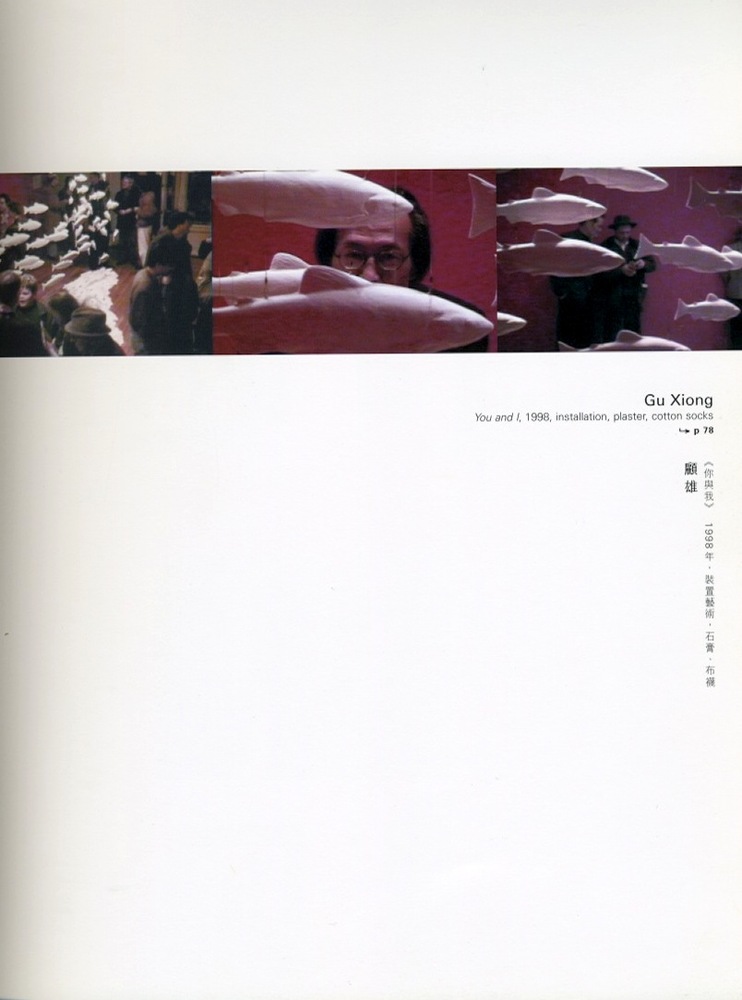

The works exhibited as part of Jiangnan brought together a variety of the subject matter, media, and perspectives that were characteristic of Chinese contemporary art in the late 1990s. Many artists synthesized traditional art forms and subject, but did so in a contemporary way in order to bring these art forms in to the 20th century. Media including fibers, silk worms, video and performance were exhibited in conjunction with contemporary expressions of traditional calligraphy and landscape painting. The works explored themes of migration, love/birth, the power of the Western art world, the construction of social control, modernist and Dadaist influences, urbanism in Shanghai and Vancouver, sexuality, and both written and spoken language. Several artists played major roles in modern and contemporary art movements in China over the past few decades: Qiu Ti and Pang Tao were important for abstract modernism in China in the 1950s, and Huang Yongping was the founder of the Xianem Dada, one of the leading grounds in avant garde art in China in the 1980s.

Zheng recalled in his talk how the president of the Chinese Academy of Art then told him how impressed he was by Vancouver audience’s reception to Chinese art. He said he had never seen a positive response on such a scale in other countries he had been to, and he felt that this series in Vancouver was one of the largest of this kind.

Sheng explained the significance of Jiangnan because of its historical relation to Yellow Signal. Even after a decade has passed the tradition continues. Last year, when Centre A invited Sheng to curate a show of contemporary Chinese art, they soon drew the same kind of positive response from other venues who all wanted to participate, remembering the success of Jiangnan. And so, what began with one single exhibition at Centre A has now grown to an exhibition series with 7 galleries and venues involved. Yesterday one more venue has joined the list: a film screen about Ai Wei Wei has now slated for the Vancouver Art Gallery, bringing the series to 8 shows.

Sheng expressed how pleased he has been to see such a reaction from other venues, curators, colleagues, the general public to the idea of bringing more artists to Vancouver so that we can understand a bigger picture of contemporary Chinese art and at what stage it is at now. The reason for Yellow Signal’s focus on new media art is a correlation that Zheng drew: Vancouver being an art centre that emphasizes photography and video, and with a long history of high quality production artists like Jeff Wall, Rodney Graham, Ken Lum, He could see that in the past Chinese artists learned alot from these Vancouver artists, while now Chinese media work has developed rapidly at an impressive rate. Yellow Signal generates the same kind of excitement in Vancouver that Jiangnan did 20 years ago, bringing these fresh, innovative works by contemporary Chinese artists here for our audiences once again.