By Jessa Alston-O’Connor

In Fire/Fire, the works of contemporary artists Marina Roy and Abbas Akhavan draw from 19th century Japanese Ukiyo-e prints of Kawabata Kyosai and Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, grounding them in the context of today’s Vancouver through animation, site-specific installation and aquatic-life in the gallery.

The tradition of Ukiyo-e prints (translated to mean “pictures of the floating or sorrowful world”) dates back to the 17th century, depicting the fantastical and the fashionable of everyday life in the pleasure and theatre district of the capital city of Edo (a city rebuilt following a great fire). The 19th century saw Kyosai and Yoshitoshi create Ukioy-e prints; methods of preserving Japanese cultural practices and spiritual beliefs during an era of growing industrialization and Westernization in Japan – a warning or concern for the future. Today, a century since these prints were made, the works by Roy and Akhavan echo those future concerns: environmental destruction and gentrification of Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside.

Kyosai and Yoshitoshi’s prints were created 100 years ago, and according to Japanese folklore, household objects come alive and self-aware (y?kai) after 100 years; prints depicting spirits and ghosts that symbolize human relationships to the environment. One-hundred is a prevalent theme in Fire/Fire. Exactly 100 years ago, the BC Electric Railway building, where Centre A currently resides, was once a bank and streetcar hub for the growing city of Vancouver.

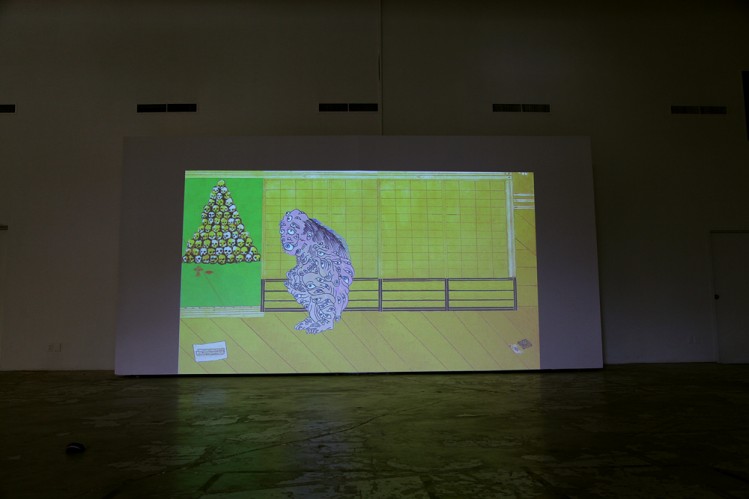

The exhibition space is sparse, two lone chairs before Roy’s video animation, mesmerizes the viewer into a 20-minute dream sequence of images inspired by her research of Ukiyo-e prints, image archives, and environmental issues. Two gurgling water tanks feature live sea creatures: urchins, sea anemones, snails and catfish, further emphasizing the ecological themes of the video’s work. Original prints by Ukiyo-e artists Kyosai and Yoshitoshi are displayed along side the gallery. Akhavan’s work explores the building itself; the shifting and cracking of the floor over time is highlighted by the fills of gold-leaf. While plywood planks over every door and window allude to post natural disasters, it’s set against an outdoor sound installation of natative bird calls.

Today, Roy and Akhavan wonder what we have done to our environment and city in this time? Where will we go from here? I sat down with Roy to answer these questions.

Jessa Alston-O’Connor: How did this exhibition take shape?

Marina Roy: Curator Andrea Pinheiro first approached me after having seen my animation and was interested in exploring these Ukiyo-e prints. I thought Akhavan would be good to bring in due to our similar interest in gentrification, ecological disasters, and distain for consumption. At first I was anxious about working with the prints, and concerned about cultural appropriation, as I am not Japanese. But with a post-identitarian idea in mind, one space affects another like an earthquake does. While these prints were created in order to preserve culture, I am interested in the shifting, opening, and deterritorialization of what the prints could mean, and the influence of Japanese prints on the West – bringing these prints into a contemporary situation. I was fascinated with the nature I saw represented in the prints and worked with ideas of human contamination in this video. I filmed oil on water as segments in the video; interested in how it spread perfectly symmetrically as though it were alive. I’m fascinated with the idea of matter being intelligent. We look at the world like we are subjects and the world is objects, but it has influence on us too. Oil is also a big topic in the news now with pipeline projects, and exploring oil flows was already something I have been doing.

JAO: Can you elaborate more about your video “One Hundred Years Later?”

MR: I researched Ukiyo-e prints in archives, selecting images that resonated with me, then removed the figures or elements to then insert my own elements and characters. I compiled thousands of images in order to create this animation. Like the 100-eye monster or the long-nosed people are rooted in Japanese prints, other are conglomerates of environmental concerns like oil, or images from past works I have made that have become my vocabulary throughout my practice. Some scenes are intentionally disturbing or gross, like the penis-headed figure I created that causes an oil spill, while other images like the farting war is taken from a Japanese print. Some images are from my childhood fascination with Big Foot, images I have seen in the media, or questions of animals migrating into the world of humans, and together they are collaged with the Ukiyo-e images – like layered images from dreams. When one spends so much time looking at images, they become part of you, part of an internal world. This video is not literal art, but a non-linear visual language, you will get a feeling, a sense of the main ideas while watching the work.

JAO: How did you and Abbas begin collaborating?

MR: We met while we were both in Victoria, working together on projects in order to keep the discussions going and [we] kept in touch. We did my first video work together and then another that looked at Victoria as a tourist site, where space is highly regulated. This brought together ideas of landscape and enclosure, questions of conquered land, of what Victoria stood for, and of how the city was portrayed. Abbas took this idea of landscape further by creating a hedge barrier in the gallery that made viewing my work difficult. He often responds to my work in this way when we collaborate, creating barriers to access the work, making the visible the invisible, disciplinary structures that control access to lands. It is a bit different here in the Downtown Eastside with building that are already boarded up, some of the best ones are deteriorating.

JAO: What directions did the exhibition take?

MR: We started with the prints, then expanded to investigate questions of environmental collapse, how cities are constructed, and urban planning as they relate to the scenes in the Ukiyo-e prints, the DTES, and the history of this building where Centre A is today. Both of us were a bit nervous about the Ukiyo-e prints, and didn’t want to be confined while working with them. Instead we wanted to reference contemporary issues too, with loose reference to the Ukiyo-e prints. The city of Edo, for instance, during the 17th century after the great fire was reconstructed to create a pleasure district. We were interested in how the DTES has become something of a pleasure district for artists; a strange entertainment district is growing here with shops, bars, and restaurants. Time passing is often key to my work. The Shinto, “We are beholden to our history, what has come before us,” resonates with me. One-hundred years [since the Ukiyo-e prints were made, since this building was a bank] is a lifetime, and a lot can be forgotten. We could have cleaned up some of the environmental issues over the years, but problems are so big now and it’s only been a century. The environment has an effect on us and ultimately, we must ask how we can sustain ourselves as a species. Are we in denial as a society because we are afraid we have no ability to solve it?