By Jessa Alston-O’Connor

Whether it is through photography, video or performance art, artist Eshan Rafi’s art explores themes of community, family, and the body. Born in Pakistan, Rafi lives on Haudenosaunee and Mississauga of New Credit territory, also known as Toronto, Canada. In 2012, Rafi participated in residencies at the Triangle Arts Association in Brooklyn, NY and at the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia. Their works and performances have been featured in numerous exhibitions in Toronto; Montreal; Brooklyn, NY; and Lahore, Pakistan.

On April 27, Rafi’s performance-based photographic work Skin will be available for auction at the upcoming 14th Annual Fundraising Dinner and Auction for Centre A, the Vancouver International Centre for Contemporary Asian Art. Founded in 1999, Centre A strives to provide a platform for contemporary Asian art that engages, educates, and stimulates a reflective experience that provokes critical thought. Over the past 14 years they have showcased over 300 artists from across Canada and around the world, and have produced over 80 original projects and exhibitions.

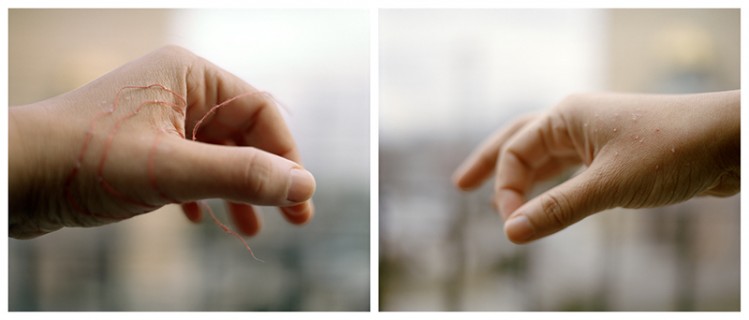

Their* performance-based photography work, Skin, is both unsettling and fascinating, begging the viewer to look closer. The work presents one hand carefully stitched with thread, the other bares the marks left behind after the thread has been removed. The comforting, domestic, and feminized practice of sewing is rendered unsettling with the penetration of the skin and the weaving of thread, and yet it is difficult to look away.

What was the impetus for Skin in particular, how did it come to be?

I was thinking about how the body can be a site of transformation. Our skin is our largest organ, the dividing line between ourselves and others. The literal landscape of the body is a place on which interventions can occur.

I had done some work with sewing on a previous project in which I sewed straight lines through family photographs that had been blown up and printed onto canvas. I became interested in how thread can symbolize continuity and relationships but also disruption.

I had also seen a still from an artist video that had wedged itself into my consciousness, but I completely forgot that that had been an aesthetic starting point until after I had made the piece. What struck me about that work was the utter banality of it. It was playful. But it got into your bones. That is what I want my work to do – get into your bones.

This work builds on larger themes of gender, and the body, can you elaborate on the role that these themes have within your practice?

My lived experience of living between genders informs most of my work. Tied to that is my relationship to my body, and specifically my body as a queer immigrant feminine racialized body.

I have often had discussions about the difficulty of constantly having to explain or justify our existence – asking for basic recognition and respect takes up a lot of of energy. Many of us – trans people, genderqueer people, feminine people, racialized people – would like the world to do their own homework so we can move on with our lives and focus on other things that matter to us. I would like to think that in my work, these experiences show up as fact – they are the underlying framework, the normative facets of my life.

Can you tell us more about your interest in the imprints on the hand left behind by the thread and the ways in which they speak to ideas of memory and location of violence within the body?

Trauma is something all of us carry, and it lives in our bodies. This became apparent to me when I began training in contemporary ballet and hip hop technique in Fall of 2011. I was learning to be aware of being in my body aesthetically and intimately and it was a difficult process. I was also accessing traditional and ancestral healing practices, such as acupuncture and yoga, which taught me that the body is the central story.

Many people in my life navigate chronic illnesses and chronic pain. It was obvious to me that living in a patriarchal, racist, homophobic, ableist colonial structure impacts those most affected by it on a highly visceral level – in the mind but also in the muscles, bones, joints, organs. We have to relearn how to be with ourselves. Skin looks at the process of taking ownership of our bodies and working with them where they are at. Transforming our futures also means honouring (not erasing) our histories.

What current projects and ideas are you working with today?

I am about to embark on a two month trip to Pakistan and have been in talks with VASL, an artist collective in Karachi, about doing a residency with them. I have so many different threads I can pick up. I would like to access dance training while I am there and work on some video pieces. The subject of hair is something I have been playing with in my work for a while and I am curious to explore it more. Hair has been such a battle for me because it is the most easily altered feature of the body and is so intimately tied to gender expression. My recent work in the fall was really about social practice and collaborating with communities and the public. I am also interested in working with my extended family, perhaps doing some portraits. Let’s see what I do next – if I choose to turn inwards or outwards or somewhere in between!

Click HERE for more information on Eshan Rafi

*Please click HERE to learn about they as a gender neutral pronoun