Programs & Events

Programs & Events

Call for Applications

Call for Applications

Centre A 2022 Arts Writing Mentorship

—

Deadline to submit: April 11, 2022, 11:59 PM PDT

Email to [email protected] (scroll down for “HOW TO APPLY”).

—

ABOUT THE MENTORSHIP

Centre A is excited to launch our 2022 Arts Writing Mentorship Program that we hope will build an inclusive community for self-identifying Asian youth while fostering a greater understanding of evolving cultural experiences and ideals. As Canada’s only public gallery devoted to contemporary Asian and Asian-diasporic art, we are committed to creating mentorship opportunities for emerging artists and cultural workers, while facilitating collaborations across local, national, and international contexts.

This 12-week program is designed to give 6-10 (maximum) young and emerging Asian Canadian writers the practice, feedback, and exposure they need to launch or grow their professional writing practice. As part of the Arts Writing Mentorship, you will receive support, guidance, and training on topics surrounding critical and creative arts writing, and how to better develop and refine your craft.

Participants will learn from established writers, editors, artists, and curators in a professional setting, while receiving exclusive networking opportunities, mentorship, supervision, and feedback on their writing. The mentorship will consist of weekly programming such as guest talks by local and international writers and curators, field trips and site visits to local artist studios and galleries, guided workshops with your main mentor(s), and peer-to-peer reviews.

As a result of this mentorship, chosen participants will produce two pieces of critical writing and get to publish their works online and in-print, compensated with industry-standard writer’s fees.

PARTICIPANT ELIGIBILITY

– Self-identifying Asian youth or young adults residing in the Greater Vancouver Regional District between the ages of 18-30; 10 (max.) participants will be chosen for the program

– Should have strong English writing and reading comprehension, with the ability to provide at least ONE writing sample (published or unpublished), i.e., Essay, article, review, blog post, or other pieces of creative or critical writing

– Must be able to commit to the entirety of the program’s duration (12 weeks)

– May be a high-school graduate, post-secondary student, or early/emerging arts professional

– Interested in contemporary art, critical writing, creative arts writing, and/or curation

– Passionate about Vancouver’s arts and cultural scenes and willing to learn, listen, and work alongside a community of Asian Canadian and BIPOC writers, artists, and curators

BENEFITS

– Hands-on experience working with established writers, editors, and curators in a professional setting, while receiving exclusive mentorship and supervision on their writing practice, and one-on-one consultations by request

– Producing two high-quality, peer-reviewed pieces of critical writing to be published ONLINE and in PRINT, compensated with industry-standard writer’s fees

– Networking and collaborative opportunities with local and international publishers, publications, art writers and curators

– Exclusive access to live in-person and virtual talks; including guest speakers such as Monika Gagnon, David Garneau, Su-Ying Lee, Yaniya Lee, Cecily Nicholson, John Tain, and Rita Wong.

MAIN PROGRAM MENTORS

Bopha Chhay is a writer and curator who lives and works on the unceded territories of the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh First Nations, also known as Vancouver. She is the Director/Curator at Artspeak, an artist-run centre with a specific mandate to encourage dialogue between visual arts and text/writing practices. She has held positions at Enjoy Public Art Gallery (New Zealand), Afterall (Contemporary arts research and publishing), Central Saint Martins College of Arts & Design (UK), and 221A Artist Run Centre Society (Vancouver). Her curatorial practice is frequently guided by a thematic query that shapes programming over the course of a year; guided by the research areas of transnationalism and diaspora, collective practices, alternative formats, art and labour, sound, independent publishing, and study groups.

Allan Cho is an academic librarian, literary editor, and community organizer, whose writings are about libraries, publishing, critical race theory, and Asian Canadian culture. Allan completed his BA and Master’s in Modern Chinese History, Master’s of Library and Information Studies (MLIS), and Master’s of Educational Technology (M.E.T.) at the University of British Columbia. As Community Engagement Librarian at UBC, Allan works closely with historically underrepresented and marginalized communities in British Columbia on cultural and heritage preservation and outreach. He is currently the Executive Editor of Ricepaper Magazine, festival director of LiterASIAN Writers Festival, and the Executive Director of the Asian Canadian Writers’ Workshop (ACWW). Having discovered through genealogical research that his great-great-grandfather had arrived in Vancouver in 1899 and great-grandfather in Vancouver in 1912, Allan is currently working on a book project on the transnational journey of his family within the context of global migration in the 19th and 20th centuries.

PROGRAM DETAILS

Location: Centre A, 205-268 Keefer Street., Vancouver, BC.

– The mentorship is a hybrid program that will be conducted both ONLINE and IN-PERSON

Duration: 12 weeks, April 28 to July 14, 2022

Commitment: The program will run once a week, 4 hours per week

Remuneration: $100 for transportation subsidies. Writer’s fee at a rate of $0.20/word for two pieces of writing (approximately 1000 words for each piece).

—

HOW TO APPLY

Deadline to submit: April 11, 2022, 11:59 PM PDT

Please submit the documents below in a single PDF file by email to: [email protected] with “Mentorship Application” in the subject line.

Your application should include:

1. A letter of intent (1000 words maximum) outlining your background and interest in contemporary art, art writing, art criticism or curation, as well as your goals for participating in the program;

2. A CV (3 pages maximum), indicating your past and current education, employment, projects, and publications;

3. One Reference (name and contact information);

4. Your contact information (name, address, email, phone number);

5. Writing Sample(s) (5 pages maximum).

Centre A values diversity because it allows us to better understand and meet the needs of the communities we serve. We encourage applications from members of underrepresented and marginalized groups, including but not limited to religion, sex, sexual orientation, marital status, family status, or disability. Due to the objective of this program, priority will go to applicants of Asian descent and racialized communities.

We acknowledge the generous support of the Canada Council for the Arts and The BC Arts Council.

![]()

![]()

Accessibility: Please contact [email protected] with any questions regarding the Mentorship program or if you require any assistance.

Centre A is situated on the unceded territories of the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh peoples. We honour, respect, and give thanks to our hosts.

Image from “Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace” (1999), part of “Asian futures, without Asians” by Astria Suparak.

Centre A is pleased to announce the Canadian premiere of Asian futures, without Asians, a new multimedia presentation by artist and curator Astria Suparak.

—

This version of the live performance/lecture is commissioned by Centre A and will take place online on Saturday, April 9, 2022, from 2 to 3:30 PM PDT.

Register HERE.

The recording of the lecture will be on view at Centre A as part of The Living Room, from Wednesday, April 27 to Saturday, April 30, 2022, during gallery hours (12 PM to 6 PM).

Organized by Henry Heng Lu

—

Asian futures, without Asians asks: “What does it mean when so many white filmmakers envision futures inflected by Asian culture, but devoid of actual Asian people?”

Part critical analysis, part reflective essay and sprinkled throughout with humour, justified anger, and informative morsels, this one-hour illustrated lecture examines nearly 60 years of American science fiction cinema through the lens of Asian appropriation and whitewashing.

Using a wide interpretation of “Asian” to reflect current and historical geopolitical trends and self-definitions (inclusive of East Asia, Southeast Asia, South Asia, West Asia, Central Asia, North Africa, and the Pacific Islands — the latter two of which are not Asia), this research-creation project examines how Asian cultures have been mixed and matched, contrasted against, and conflated with each other, often creating a fungible “Asianness” in futuristic sci-fi.

The quick-paced performance lecture is interspersed with images and clips from dozens of futuristic movies and TV shows, as Suparak delivers anecdotes, trivia, and historical documents (including photographs, ads, and cultural artifacts) from the histories of film, art, architecture, design, fashion, food, and martial arts. Suparak discusses the implications of not only borrowing heavily from Asian cultures, but decontextualizing and misrepresenting them, while excluding Asian contributors.

ABOUT THE ARTIST

Astria Suparak is an artist, writer, and curator based in Oakland, California.

Her cross-disciplinary projects address complex and thorny issues (like white supremacy, colonialism, and racial capitalism) made accessible through a popular culture lens (such as sci-fi movies, rock music, and sports). Straddling creative and scholarly work, the projects often take the form of publicly available tools, databases, and histories of subcultures and omitted perspectives.

Over the last year Suparak’s creative projects have been exhibited and performed at MoMA, ICA LA, The Walker Art Center, The Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts, and as part of the For Freedoms billboard series. Suparak has curated exhibitions, screenings, and performances for art institutions and festivals including The Liverpool Biennial, Museo Rufino Tamayo, The Kitchen, Eyebeam, MoMA PS1, and Expo Chicago, as well as for unconventional spaces such as roller-skating rinks, sports bars, and rock clubs.

Centre A would like to acknowledge the funding support of the BC Arts Council for this project.

Accessibility: The gallery is wheelchair and walker accessible. If you have specific accessibility needs, please contact us at (604) 683-8326 or [email protected].

Centre A is situated on the unceded territories of the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh peoples. We honour, respect, and give thanks to our hosts.

Saturday, March 5, 1 – 3 PM PST

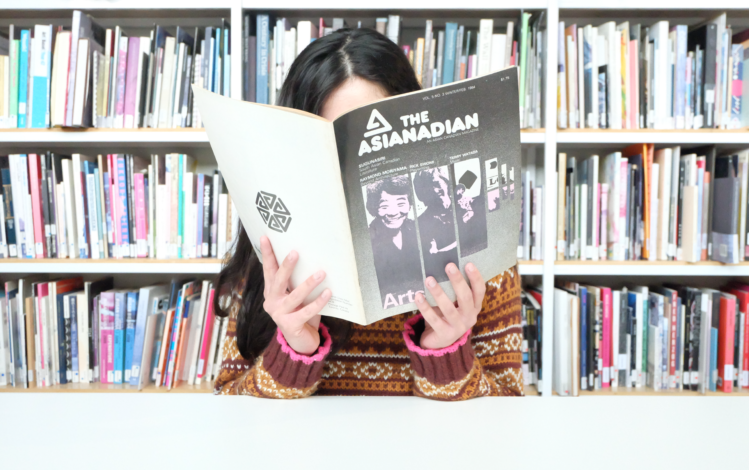

In conjunction with Centre A’s current exhibition Revisiting the Asianadian, we will be hosting another iteration of the Centre A’s Reading Group on Saturday, March 5, from 1 to 3 PM. We will be revisiting the history and development of the Asianadian Magazine in the 1960s and 1970s, connected to themes of Canadian Asian-diasporic identities, racism, social justice, and activism.

For this reading group, we will be reading the following text:

- “Asiancy and Visual Culture: The Asianadian Magazine 1978–1985” by Dr. Alice Ming Wai Jim (Journal of Canadian Art History)

- “Ten years of Asian Canadian Literary Arts in Vancouver by Jim Wong-Chu” (The Asianadian Magazine, Vol. 5, No. 3)

Revisiting The Asianadian is a rare presentation of the entire run of The Asianadian Magazine, a quarterly publication in Toronto from 1979 to 1985. The publication was a key witness to some of the defining moments in Asian Canadian cultural history during the time.

Spaces are limited! Sign up for the event at [email protected].

—

The reading group aims to support artistic and curatorial engagement by creating a space for exploring themes of the exhibition through alternative methods.

The reading group will take place in our gallery space at Unit 205, 268 Keefer Street in the Sun Wah Centre located in the historic Chinatown on the Unceded Territories of the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh Nations. We will be limiting the reading group to max. 15 participants and will be following COVID-19 protocols. The readings will be sent out a week prior to the gathering.

Participants of all levels and experiences are welcome!

—

Notes Regarding the Event:

- Be gently reminded that, in accordance with the Provincial Health Officer (PHO), you are required to bring proof of vaccination and your ID to attend events at the gallery. Face masks or face coverings are necessary when you are in the gallery space. We also encourage you to sanitize your hands before and after visiting. Masks and hand sanitizer are available for you as needed.

- Due to Sun Wah Centre’s security measures, please locate the security guard posted at the front gate to be let into the building. Otherwise, please call Centre A at (604) 683-8326 during the event hours.

- Centre A is wheelchair and walker accessible. If you have specific accessibility needs, please contact us at the phone number above, or via email at [email protected].

Centre A invites participants to our virtual and in-person Art + Feminism Wikipedia Edit-a-thon. We are collaborating with the Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery to bring forth stories that too often go unacknowledged in the art world. Help balance the imbalance by creating and editing Wikipedia articles about women, LGBTQ2S+, gender non-binary, people of colour, Black and Indigenous artists, curators, and organizations as well as feminist and activist art movements. In this event, we would like to focus on feminism through an intersectional lens that acknowledges a multiplicity of lived experiences including, race, class, privilege, disability, and sexuality.

Please join us in reconsidering representation and community in the open-source knowledge platforms. We will provide help for beginner Wikipedians, reference materials, and technical support for making your edits.

Centre A strongly encourages individuals with diverse backgrounds and narratives to participate.

—

Join Centre A for the following virtual and in-person events throughout the month of March!

Saturday, March 12, 2022, 12 – 1 PM PST: Virtual Workshop: How to Navigate Centre A’s Database Workshop

Come join Diane Wong, Centre A’s Library and Exhibitions Assistant to learn about the history of Centre A’s Reading Room and how to navigate our online database for the Art + Feminism Wikipedia Edit-a-thon.

The Reading Room and library at Centre A began in 1999 with contributions from artists, researchers, and curators both locally in Vancouver and internationally. The Reading Room emerged out of the need to collect a body of literature on Asian art practices, and by extension creating transnational ties with international arts communities.

Saturday, March 19, 2022, 12 – 3 PM PDT: Virtual Q&A Drop-In with Centre A

Do you have any questions or require any support regarding the Art + Feminism Wikipedia Edit-a-thon? Drop in to our virtual Q&A and a member of the Centre A team will answer your questions!

Saturday, March 26, 2022, 1 – 4 PM PDT: Art + Feminism Wikipedia Edit-a-thon at Centre A

Refreshment and childcare will be provided. Please bring an electronic device you can edit on. If you require childcare, please email [email protected] before Saturday, March 19, 2022.

Sign up for the Virtual Workshop and in-person Edit-a-thon at [email protected]

Can’t make it to the events? Check out these online guides and videos or visit Art + Feminism’s website.

–

New to Wikipedia editing?

- No Wikipedia editing experience is necessary.

- Wikipedia training, reference materials will be provided.

- Workshops will be provided at the Edit-a-thon event & at How-to-edit training workshops before the event (see details below).

You can first join the following virtual workshops with the Belkin Gallery on:

- Thursday, March 10, 2022, 1-2 PM PST: Introduction to the Wikipedia Edit-a-thon and How to Get Started with Sara Ellis and Jay Pahre

- Tuesday, March 15, 2022, 1-2 PM PST: Citations How-to Workshop with Sara Ellis

Find more info about the workshops and additional events here

To RSVP for the workshops email the Belkin at [email protected]

Notes Regarding the Event:

- Be gently reminded that, in accordance with the Provincial Health Officer (PHO), you are required to bring proof of vaccination and your ID to attend events at the gallery. Face masks or face coverings are necessary when you are in the gallery space. We also encourage you to sanitize your hands before and after visiting. Masks and hand sanitizer are available for you as needed.

- Due to Sun Wah Centre’s security measures, please locate the security guard posted at the front gate to be let into the building. Otherwise, please call Centre A at (604) 683-8326 during the event hours.

- Centre A is wheelchair and walker accessible. If you have specific accessibility needs, please contact us at the phone number above, or via email at [email protected].

In Conversation: Embodied memories and artistic practice

A conversation between artist Cindy Mochizuki and Centre A’s former Curatorial Assistant Intern Alexandra Tsay.

Vancouver-based artist Cindy Mochizuki has exhibited with centre A twice: first in the group exhibition To|From BC Electric Railway 100 years in 2012 and recently in the group show A Lingering Shadow presented at the Polygon Gallery in partnership with Centre A in August 2021. Cindy’s works are devoted to exploring the history of the Japanese diaspora in Canada, the collective and personal memories of the political violence, and the injustice toward the Japanese community. Her works remind me of the shared experiences of diasporic communities around the world in displacement, forced migration, and the beauty of hybrid identities. I have been interested in how art can act as a medium for memory and artistic work with memory for a period of time, and I was delighted to meet with Mochizuki to talk about her artistic practice, the ways she engages with personal and collective memories, and Japanese folklore.

Since the 1970s there has been a ‘memory boom’ in academia with scholars of various disciplines from literary criticism to cultural anthropology engaging with research on collective, personal, and public memories. Memory as a narrative in art has seen growing numbers of artists and practices examining and engaging with the discourses of how and what we remember and forget, what was forgotten, and what should be remembered. Scholars have been producing discourses on critical memory that reflect on collective practices of remembering past injustices to prevent similar events happening in the present or future. Silenced histories are complicated objects to approach. Both structures of public institutions and agencies of researchers, scholars, and activists do the work of repair, remembering, reconciliation. What can art do that cannot be done by other means? Why art?

Cindy Mochizuki: In my practice, I explore and look at the history of Japanese Canadians. I often work with Japanese Canadian seniors. They are now in their 80s or 90s, some of them are part of my family while others are not. These nisei (2nd generation Japanese Canadians or sansei (3rd generation) were in internment camps at the age of three or four years old. Annette Kuhn’s memory work is called to attention here in my practice, where you are actively engaging with remembering and forgetting, my practice has a large part of this process. I often think of the artwork as a creature; there is a face, or the very public side of the art exhibition, but I also have a large part of work that is behind-the-scenes – its backside or tail. As part of this process, I’m meeting with seniors who do not remember or do not want to remember. I do not want to force them to tell stories, but usually, after I start meeting them and building these relationships, I will receive tons of emails and phone calls like “Hi, I am from Hawaii, I want to tell a story about my berry farm in Fraser Valley for your project.” They come to me and share their stories and through this act of sharing and retelling, they are engaging with processes of remembering and transforming these stories.

Alexandra Tsay: I was always curious about how art can be a medium for memory, and one of the reasons memory can be captured through art is probably because memory reflects on the fragility of human beings. We cannot be sure of what we remember or forget – our memories can still be lost no matter how hard we try to preserve them, and it is one of the biggest wonders and joys to have unexpected flashbacks in their full colour. But somehow it is this beauty of memories, why they stay with us and how they stay with us, that through art we can access something that has been lost.

C: Yes – memory is fragile, unstable, slippery. In 2017, I made a video called Lines to Remember as part of a project called dawn to dust and it is of my aunt’s drawing of the house where they lived in Japan after the internment. In the video they draw a house from memory. My father’s family ‘chose’ repatriation after they were in these camps from 1942 to 1946 and after the war was over, the Canadian government had sold their property, so they had nothing to come back to and had two choices: to be paid to get to Japan or east of the Rockies. My grandfather’s family decided to do the forced exile to Japan from 1946 until the early 1960s.

Their bodies were read and perceived as Americans in Japan, and the Americans were seen as enemies during WWII. There was this feeling of unacceptance of these racialized bodies because they were not accepted in Canada, and they were not accepted in Japan. They had found themselves in between both of those cultures, not truly belonging anywhere. For me, when I want to know that history, the history is coming from those bodies. It is an affective, embodied, lived history. It is a memory work that, like memory, is slippery. It can hide some things, but it also reveals something unexpected and very human.

Food and memory

A: When you were talking with people about their life in Fraser Valley for your exhibition Autumn Strawberry (2021), was there something they recollected more often, a recurring theme that came up in people’s stories?

C: A lot of stories that people retold and remembered about their life on the farms in Fraser Valley before the war were about food or food preservation. I have gotten a lot of recipes of what women who ran the farms cooked, or seniors who were kids at that time telling me about what their baachan made, and what tofu tasted like on their farm. One woman came to the studio and shared her tsukemono, Japanese pickles. There was a different recipe and technique each time. I thought it could be a whole new project. Food is such a big part of childhood memories – the warmth and joy of it. I also think that food can be a mode of survival in that case; a lot of mothers would feed eight-plus children and workers and they always planned the cooking and meals. But also, there is a connection between food and memory, and how taste and smell can suddenly evoke a series of memories.

Familial memory or memory transfer inside families

A: Were the descendants of the people with whom you met aware of the stories of their grandparents? Or was it something they had just opened up?

C: They are aware of the project and interested in taking part in the process. Daughters and sons would drop off their elderly parents or also stay for the story sharing. Some of them know these stories in great detail, some vaguely know about the history, and some of the younger generations who took part don’t know a lot about their grandparent’s stories, but are willing to learn and understand. When they see their parents or grandparents talking to me about specific moments or memories, it is an awakening for them as well.

A: There is a kind of generational gap in working with trauma; grandparents or parents may not have shared this with their children because they did not want to traumatize them, or chose to carry on. But they can still transfer their traumatic experience anyway through behaviour, through unspoken means of communication within families, and it is one of the reasons why repair work is still important.

C: I don’t think ‘performance’ is the right word – but there is a strong performative element to memory work. One of the participants brought her mom; the daughter was hesitant and even texted me that her mother would probably not say much and not be helpful to the process. But when we met and asked questions, her mother talked and talked, retelling small details and nuances – she went on for hours. Something happens inside this work. It is very special for me to hear that some participants did not expect to see their parents being so open and willing to tell their story, which I think speaks to the power of art.

Repair work

A: What does repair work mean for you? Is it an opportunity for people to open up, to share, to retell their stories, to live them again, and to feel all those emotions? When it enters the art realm, does it also become the collective repair work as a part of its shared history?

C: As part of Autumn Strawberry we had asked the descendants of some of these storytellers to return back to the installation to work with the choreographer, Lisa Mariko Gelley on simple movement sequences. These sequences were taken from the animations about the stories of their parents or grandparents, which can also be seen and heard in the installation. This aspect of the project re-grounded these embodied memories back into the body in new forms and new energies. The bodies get to return and most importantly play. All of the participants are not performers but there was a collective understanding of why we were there making this work and that there was a collective trust in the process to work through it.

Memory, identity, and Japanese folklore

A: Through your work, it feels like a connection with Japanese culture is important to you. How do you approach Japanese culture and folklore? Are you aiming to activate new meanings there or do you want to create your own versions of mythological stories?

C: I have worked on a few projects in Japan, specifically Yonago, Daisen, and Akita, where I have really explored those aspects of Japanese culture. There have been uncanny situations; when I was a kid I used to have terrifying nightmares here in Vancouver. In my dream, a Buddhist chanting crow would open my mouth, go inside, sit in my head, and chant. These were forms of kanashibari. A few years ago, I was invited to do an artistic residency in Daisen in Tottori-ken. It is a rural village and has heritage sites where they invite artists to produce works and community projects as a means to preserve the heritage of these spaces. It is a small community of artisans and farmers. The curator of the residency wrote to me to say “we are having such a down year and those in the community want you to come and do a project around fortune-telling to uplift the town.” When I arrived in the town, I saw the image of the Karasu Tengu everywhere. He is a character from Japanese folklore that is half-human and half-crow. He is said to be able to shape-shift into a Buddhist monk, is a bit of a trickster, and can bring about change. It was revealed that this region was protected by this figure, and it was that same crow from my childhood nightmares! As a child, I saw and felt a lot of these creatures and cosmologies and it can be based on what and how my parents passed down songs and stories. My father was Japanese Canadian and my mother was born in Osaka and grew up in Yokohama, Japan. Now, as an adult, I came to know these signs as Japanese folklore, but as a child growing up in the Western context, I think you suppress these aspects of Japanese heritage and mythologies or there is no context for them. I was wondering what these dreams were? In that residency, I prepared and read coffee readings for the community and did automatic paintings of what I saw, these paintings were then gifted to each participant. I worked with seniors who harvested organic materials like flowers, plants, et cetera to make a palette of colourful inks. We created a theatrical set of a large Karasu Tengu’s head and I sat with participants who were complete strangers and read their possible futures.

A lot of my work focuses on the past, but then I am also very interested in future tellings, improvisation, divination, and storytelling. During this residency, my drawings for each participant ended up becoming a part of an experimental animation that was more like an archive for the participants to return to. The exhibition took place in an abandoned sake kura, and they would return to the films to find their futures. They called it the archive of the future. Then actually… Years later, three-quarters of those future possibilities came true.

Cindy Mochizuki creates multimedia installation, audio fiction, performance, animation, and drawings. Her works explore the manifestation of story and its relationship to site-specificity, invisible histories, archives, and memory work. She has exhibited, performed, and screened her work in Canada, US, Australia, and Japan. Recent exhibitions include the Vancouver Art Gallery, Burrard Arts Foundation, Richmond Art Gallery, Frye Art Museum, and Yonago City Museum. She was the recipient of the Vancouver’s Mayor’s Arts Award in New Media and Film (2015) and the Jack and Doris Shadbolt Foundation for the Visual Arts VIVA Award (2020).

In Conversation: stories and myths we tell ourselves about ourselves and others.

A conversation between artist Lucie Chan and Centre A’s Curatorial Assistant Intern Alexandra Tsay.

Art is a mythology of our currents––some art, some currents. Myth is a traditional story of allegedly historical events that serves to unfold part of the worldview of people or explain a practice, belief, or natural phenomenon. In the past, people used myths to make meaning out of the mysteries of the world they lived in, or to explain the world to themselves through the stories of gods and supernatural creatures. The world has transformed, changed, and happened to be a less enigmatic place, but contemporary artists use art to remind us there are still mysteries in the world we live in. Human beings are one of them. I believe the narrative of art as the mythology or the body of alternative knowledge that unfolds, explains, examines, and questions the current moment is one of the frameworks to look at, experience, and appreciate works of contemporary artists, and Lucie Chan is one of them.

I met with Lucie over Zoom; the pandemic over the past year and a half proves that online conversations can still feel unexpectedly warm as a real encounter (do we know what is real anymore?). Lucie is a Guyana-born Canadian artist and a professor at Emily Carr University of Art and Design. She presented an exhibition, To Be Free, Everything You Most Hate and Fear?, at Centre A in January 2020. Lucie creates assemblage-like objects combining various artistic media and materials into both grandiose and fragile installations. We have talked about her artworks and what inspires them, about what it means to see and be seen, and how signifiers of identity both reveal and hide who we are.

“My art reveals a mass confusion of being a human being.”

Lucie: Sometimes I feel that people want to put me into a specific box or a particular way of thinking about things. My work is often about retelling stories. I have had a long career of interviewing strangers and sometimes people I know. I am interested in these interactions when something is revealed that we don’t necessarily have every day like a sense of connection or intimacy that doesn’t exist or is impossible to happen if you live in a big city because we are humans, and we have boundaries and mutual expectations.

I am interested in the translation of what happens when I interact with people who do not necessarily have their voices heard in an intimate way. Instead, I have always been interested in what you are not supposed to do. You are not supposed to retell the stories of others, and I have always been interested in that, because I think there is something about oral histories and carrying someone else’s narrative in order to try to create some really deep work that embodies these stories. I really treat time together as beyond research, as process. I am thinking of how without art I would never have this and without that person I would have a harder time to change as an artist.

Alexandra: How do you meet those people? How do you choose them?

L: It starts with choosing the interviewees. I am very introverted and shy; for months and months, I can just observe people in the library or at my community gym that I think look interesting. I do the exact thing that I hate people doing to me: people think she looks interesting, she looks ethnic or looks like she is from somewhere else. I reversed the role. I am trying not to ask friends for conversations, instead, I am trying to ask people who don’t know me — that way, we don’t owe each other anything, we are strangers, or in artistic residencies I invite people, and we don’t know much about each other, but we just sit and talk, and for me, as a shy person it’s amazing that people sign up to do that.

A: What are your conversations about? Do you have a prepared set of questions or is it a spontaneous dialogue?

L: Sometimes I have prepared questions that I don’t quite know the meaning of. For example, once the question was: teach me a cultural lesson. I was in Canada at the time, the people I interviewed were all from different backgrounds. We immediately laughed together, and they opened up and told me things I have never heard of.

When I was in Halifax, no one would believe that I have the last name “Chan” and that I could possibly be half Chinese. But then I said: “Teach me or make me more Asian”, and we didn’t even know what that was. There were Chinese, Korean, Japanese people, immigrants and Chinese-born Canadians, and we were just talking about how or if Asian culture could include this: when we just go to the yard and lay on our backs and scream and be really inappropriate and have an hour of that a day. Could it be Asian? What does it mean to be Asian? Those questions were a bit traumatizing for me, because people could look at my skin or grab my hand and ask what part of China I was from, what my Chinese name was.

I realized that people I was speaking to were taking risks by exposing something about themselves, too. They were telling me that, “We are not interested in this, because we are not just Chinese or Japanese or Canadians, we are so much more.” I am interested in that, and ways in which we can arrive somewhere else. We are all immigrants in Canada, no one is similar to another person. I am more interested in those nuances and surprises that are not always on the surface or great; it’s awkward. I think it’s important to sit through that too. I think it is a part of problem-solving through art.

A: How do you translate those stories and encounters into artistic practice?

L: Writing is a huge part of my process; I sit and write, and have a very condensed narrative. For a long time, I would ask different people to read these narratives, and because of their accents, or because they went through something similar, they all sound different. It is actually very beautiful, as we read these stories out loud to a young person, and they imagine something. I create installations with different images, sculptural elements, photographs, and audiovisual elements as well. I am trying to combine different artistic elements to reveal the complexity of being human. The translation always shows multiple aesthetics and connections and fused relationships between aesthetics — sound, video, image and that is the way of showing how layered and complex people are. My art is about the mass confusion of being a human being.

When I ask people to teach me a cultural lesson, we can meet several times and talk, and when the project is done, I spend more time sitting and talking to them further. I think it is a cultural lesson to talk to a person about not simply about where they were born, or if their parents were first-generation immigrants. It is obvious to us, but not everyone sees and understands that cultural identity is not actually the core side of people.

A: Do you think that, for an immigrant or an immigrant artist, it is possible to be seen out of that cultural box? You are seen as a part of your bigger identity whatever it is, whatever people have in mind and then if you want to jump out of that box it can be very difficult.

L: I immigrated here at a young age, I always looked at my parents and thought about how difficult it must be in your early 30s, to leave your home country, have two kids, leave behind almost all of your belongings and move to a new country. It is difficult even at a young age. If you are an immigrant, it is difficult to be seen outside of your box, or what people think you are bringing with you, or what you embody. I really think it is one of the most essential human experiences, especially in Canada. I moved here in the year of the Multiculturalism Act, so suddenly, that was on my mind from a very young age. Now I see that people of different ages, have never been seen or are seen through very specific frames. I think it is my responsibility as an early immigrant to say that it is essential for Canadians and immigrants who arrive here to have a choice of what they can be and what their life could be.

A: Can art help with breaking those frames of seeing each other and opening new ones?

L: I am a teacher, so I bring in artists who represent some of the students who don’t usually get to be represented, and they come to me and say: “I didn’t know you can be from the Philippines and make art about the Philippines” or “I didn’t know you can be from Salvador and make art about your country.” For me, it’s a heartbreaking and important moment to realize how essential it is that we are not stuck in a bubble and let people create whatever they feel needs to be created.

I truly feel it’s one of the most critical things and I thrive not only as an artist but as a teacher — I tell my students to not only look at artists who are taught within the canon, but also look at the amazing things that people have been doing for ages before Canadians have been doing this.

A: Why is drawing important for your practice? Was it somehow connected with stories? Is there any connection between stories and drawing?

L: It started as a very practical thing, I was at the art school and I liked animation, sculptures, and drawing. I liked the idea of drawing because I wasn’t rich. I actually didn’t have much money, and I was afraid when I left art school I wouldn’t be able to be an artist because I didn’t have any equipment. I just said to myself that I didn’t want to go out into the world after that special time in art school and not have access to those things and not be able to make things. Drawing was something that people usually do before they move to the next thing and people usually say to me: I have all those beautiful papers from when I used to draw, but now I am making sculptures. All these drawing materials came to me freely, and I didn’t buy any supplies for about five years after graduating from school. People were giving them to me.

Now I think there is something very powerful in drawing, it allows you to be very humble in response to materials in a way that what you did when you were very young. When I started drawing I didn’t have a plan, I had ideas, but it is not like a recipe, it is more like a slow process that doesn’t connect with the outside world. It is like a meditation and I like to start as an exploration of what a drawing can be instead of drawing as masters did.

A: Did you draw from a young age?

L: I have been drawing since I was young. When I was bored and I wanted to go outdoors to play, my father made me write or draw, maybe related to his own visual and writing practices, but also to keep an eye on me.

A: You somehow also combine storytelling, voices and sound,

L: Yeah, my father didn’t go to art school but was always creating and being inventive in all aspects of his life, and I didn’t know that being an artist is something you can do seriously. My surroundings had an impact on all of my senses. Maybe indirectly, even though our works look very different, I am affected by stories, voice, sound. Thank you for making this connection for me.

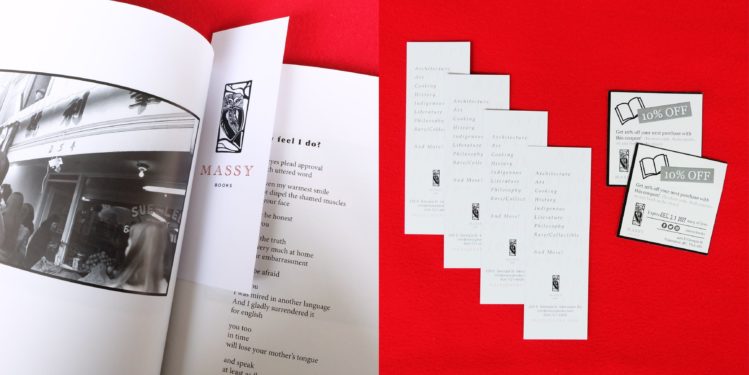

We are super excited to collaborate with community partner Massy Books for our new membership perks! Anyone who signs up for a Centre A Membership will now receive a 10% discount off their next Massy purchase with a coupon, valid until December 31, 2022.

Use the free bookmark included in your membership for your upcoming reads! Pictured here is Chinatown Ghosts: The Poems and Photographs of Jim Wong-Chu, which you can find at both the Centre A Reading Room and Massy Books for purchase.

ABOUT OUR MEMBERSHIP

New applicants who sign up for Centre A’s membership will receive the following benefits:

– Priority to pre-order any new Centre A publication

– Priority access to any new items (including publications) at the Centre A Boutique

– 10% discount on any items at the Centre A Boutique

– Subscription to our monthly e-newsletter

– Voting privileges at our Annual General Meeting

– Donation receipts for any donation $20 or above

– A 10% discount coupon with Massy Books and free bookmark

MEMBERSHIP PRICES

Students Membership: $10

Regular Membership: $20

TWO WAYS TO BE A MEMBER

– Sign up via the link in our bio

– Contact us at [email protected] (if you have any other questions about our membership)