Vancouver International Centre for Contemporary Asian Art

Alvin Luong: Dispatches from Bidong

Dispatches from Bidong

Dispatches from Bidong

Presented by Alvin Luong

August 2, 2023

Multimedia (video and text)

–

In June, artist Alvin Luong visited Pulau Bidong, a small island in Malaysia that formerly hosted thousands of Vietnamese refugees in the aftermath of the Vietnam War. The crowded refugee camps on Bidong once made the island one of the most densely occupied places on earth. Today, few traces remain of the camps on the paradise-like island.

Over the course of the summer, the artist will share a series of reflections, images, and recordings related to Pulau Bidong. This project builds on the artist’s practice of creating artworks that reflect upon historical development and its intimate effects on people’s lives.

–

Dispatch #1/6 from Bidong

In June 2023 I visited Pulau Bidong, a small island located off the east coast of the Malaysian mainland. The island once hosted tens of thousands of Vietnamese refugees who had fled Vietnam towards the tail end of the America-Vietnam War (1955-1975) and its aftermath. I was drawn to the island because my father was among one of the refugees who lived on Bidong. I have created artworks, like “Hole Story” (2023) and “Ration Market Special” (2022), by reinterpreting my family’s oral history of surviving the War to anticipate how people in Vietnam may fare in a future severely impacted by climate change. Building off of this trajectory my trip to Bidong is a next step to form the conceptual foundations for new artworks. Little information can be found about the history and contemporary state of this significant site. So I hope that these reflections may provide elucidation for others interested in Bidong and also give insights into how I process the world through my practice. These reflections of primary research stem from oral histories shared to me by my tour guide Alex, from my own experiences traversing through Bidong, and cross references with my father’s experience living on the island.

The first wave of refugees had originally arrived on the Malaysian mainland by the port town of Merang and its surrounding sea shores in the state of Terengganu. By 1978, the number of refugees arriving to Malaysia had grown dramatically which led the Malaysian government to relocate the refugees to Bidong and to allocate the island as a sanctuary zone for further incoming Vietnamese. The refugees lived on the island from months to years to find sanctuary in other countries through humanitarian immigration and asylum programs. These countries included Australia, Canada, and the United States of America. Life on the island was partially self-sustained through the labour of the refugees themselves to build and maintain the camps using materials like wood that was scavenged and extracted from the forested mountain of the island. More robust materials needed to fabricate the camps such as metal, concrete, stone, and pipes were imported from the Malaysian mainland. A long undersea pipe was built between the mainland and Bidong to supply freshwater to the camps. In terms of sustenance, some food was grown on the island or caught in the surrounding ocean waters yet the majority of the food was imported from the mainland.

–

Dispatch #2/6 from Bidong

Today, the majority of the camps have disappeared from the repurposing of materials, decades of decay, and the regrowth of the non-human ecosystem of Bidong. A small number of people now visit the island including recreational campers, scuba divers, marine biology students, people like me, and groups of former refugees who make yearly pilgrimages back to Bidong to pay their respects to those who had passed away on the island and to keep the place clean. I’ve come to learn that taking care of the island and preserving what remains of the former camps is a labour carried out by volunteers who typically visit the island during the Grave Sweeping Festival (Qingming Festival). Organized trips and historical tours to Bidong are also mostly conducted by word-of-mouth and are advertised in a subtle manner because the island is embroiled in a geo-politically sensitive situation. Preserving and sharing the important humanitarian history of the island is a point of friction between the Vietnamese and Malaysian governments who are strategic partners in Southeast Asia. The island reveals a side of history that is disharmonious with the contemporary national project of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. These factors make it difficult to find clear instructions to reach the island.

It takes about two-and-a-half-days to reach Bidong. First, I traveled to Kuala Lumpur, the capital of Malaysia with an international airport. Aftwards, I traveled to the coastal city of Kuala Terengganu, the largest city with a regional airport in proximity to Bidong. Bidong can be seen from a distance from the coasts of Kuala Terengganu. I began the last leg of my journey to Bidong with a chartered van ride from Kuala Terengganu to the nearby port town of Merang where a chartered boat would take me to the island. The boat ride from Merang across the sea to Bidong lasted approximately thirty-minutes. I was accompanied by my guides Alex and Darrius; as well as the boat captain and his child. As the Malaysian mainland faded from our view we were surrounded by the vast ocean. It is hard to imagine that people had once packed themselves on boats and sailed for days to reach Bidong. Overcoming the ocean was itself a mortal challenge before even setting foot in the camps.

–

Dispatch #3/6 from Bidong

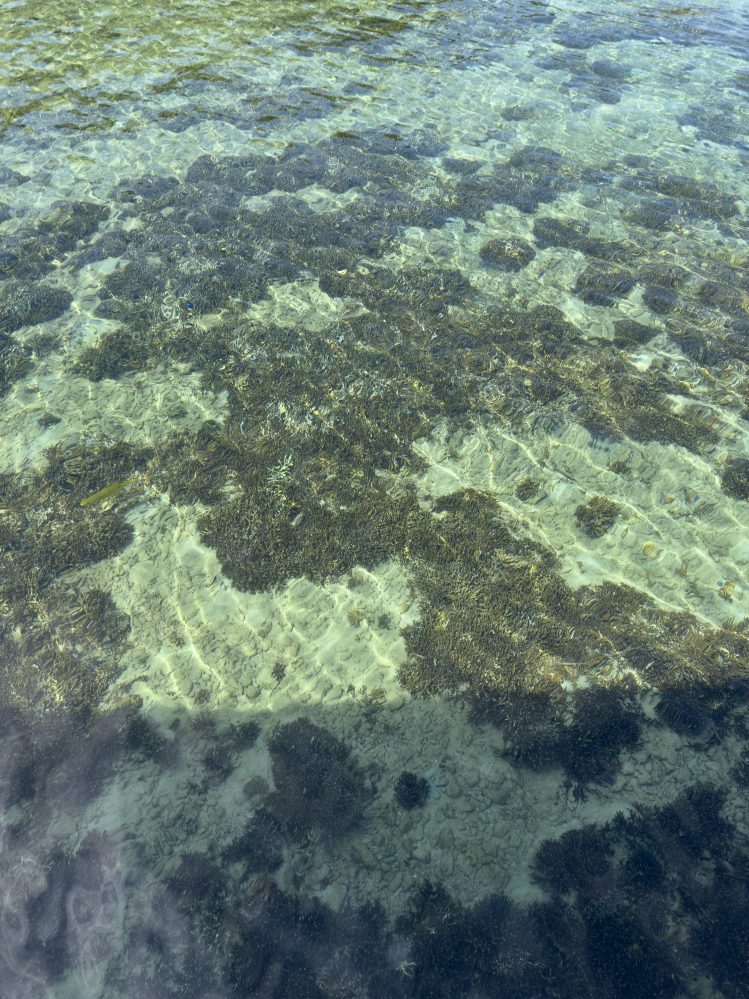

When we reached Bidong we docked on a newly built jetty. Tiny fish swam in the deep blue waters around the boat. Dark blotches were visible below the surface of the water which indicated that corals had repopulated the seabed of Bidong. On the beach shore several small buildings had been recently constructed to support attempts to use Bidong as a recreational campsite and as a fishing ground. Behind the beach was a grassy field and further behind that was a forested mountain. Punctuating this scene of paradise is a rusting metal ship that had been abandoned on the beach by the refugees. Decades of corrosion from the ocean water has given the ship a skeletal appearance as if it were an omen for the history of the island.

–

Dispatch #4/6 from Bidong

The terrain of Bidong features steep rocky cliffs that rise from the ocean with the exception of two connected beaches on the southern tip of the island. These two beaches provided the level terrain required for people to live on the island yet also corralled them into a dangerously crowded situation. Thousands of people lived in makeshift camps; plumbing and water systems sprawled across the island floor; and graves still dot the higher grounds of the mountain. The former presence of the camp buildings can be witnessed from exposed structural foundations made of concrete or brick that occasionally protrude from sandy or forested floors. When Bidong was a refugee camp the island was partially deforested, the fish were gone, the water was murky, and the corals had disappeared. It was hard to imagine all of this from where I stood on the pristine beach.

On the eastern side of the beach is a set of aged concrete stairs that lead up to a natural rocky cliff which faces the ocean. This area hosts a large monument that was built by the refugees in the shape of a sail and a boat. The monument features inscriptions in Vietnamese, Malay, and Chinese that express gratitude towards the island and pays homage to those who had passed away in their journey to the camps and while living in them. Around this monument are several concrete altars and religious statues. These religious fixtures were once enveloped inside buildings that had by now disappeared. The area is also the curious site of many stone plaques that have been adhered onto various rocks by former refugees who had returned to Bidong. These plaques often denote the former refugee’s name, the identification number of the boat they had used to get to Bidong, where they had resettled, and the date of their return to Bidong. These plaques announce to others that they are not alone in their experiences of Bidong.

–

Dispatch #5/6 from Bidong

Connecting the commemorative and religious area is a forested trail that leads to the foot of the mountain. Abandoned drinking water storage facilities are found along the trail and further up the trail are grave sites belonging to those who had passed away on the island. These graves are regularly maintained by visitors who trim the encroaching grass and maintain the tombstones. Foil wrapped biscuits and empty shot glasses were recently left behind by visitors paying their respects. The tour guides and I took a detour from the trail and hiked down a steep slope that was formed from a pile of garbage that accrued from the camps. Soil, small plants, and tree roots intermixed with occasional bottles and woven plastic tarps that protruded from the ground. At the bottom of the slope was the second beach. This beach had many newly constructed recreational camping structures, a coral growing facility, and very pristine sand. Sea turtles lay their eggs on this part of the island which in turn has prompted the Malaysian government to consider designating Bidong as a protected national park. If Bidong becomes a national park then the recreational camping facilities will be removed and access to the park will become easier.

–

Dispatch #6/6 from Bidong

The guides and I returned to the first beach by climbing a cliff that led us back to the commemorative and religious area. From there we walked back to the jetty, undocked the boat, and left Bidong for the Malaysian mainland. As we sailed back to the port town of Merang my guide Alex informed me that across the river from our dock was the former site of the first Vietnamese refugee camp in the area that formed in the late

1970s. Several informal grave sites were also set up along the beaches by Merang belonging to the earliest waves of refugees who did not make it through the sea voyage to Malaysia. This all occurred before Bidong was transformed into the designated landing and living area for the Vietnamese refugees.

I have mixed feelings about visiting Bidong. I knew beforehand the island is a place where people had faced the lowest points of the human condition. This knowledge created for me an expectation that one should experience the place through an austere pilgrim-like sorrow. Yet despite this, I had a rush of excitement and a complex joy when I journeyed through Bidong. As an artist my experience of Bidong was heavily mediated by a duty to feel, witness, and learn about the history of the island and also its contemporary state. The appearance of paradise on the island and the presence of the occasional fisherman or recreational camp staff changed my whole perception of Bidong. The emotional register of Bidong alters as history is allowed to pass through the island with the disappearance of the camps and the new uses of the island. If the Bidong were to be fully “museumified” with anachronistic preservations or reconstructions of the camps then the fate of the island would be predetermined. The material changes of Bidong in the regrowth of its non-human ecosystem and the edification it brings to recreational campers, scuba divers, marine biology students, and a curious artist all signal that the futures hoped for by the refugees may have arrived.

My thanks to Centre A for supporting the trip to Bidong and to Henry Heng Lu for inviting and encouraging me to conduct this life altering journey. I would like to acknowledge my tour guide Alex who has for decades worked to support the healing and self-discovery process of former Bidong residents and their descendants. Since the 1990s, Alex has facilitated journeys to Bidong and has become an unofficial historian of Bidong through the oral histories that are shared with him by countless visitors. Fate has assigned a strange duty to Alex to which I am grateful that he has dedicated a large part of his life to continuing.

–

Artist Biography:

Alvin Luong works with stories of human migration, land, and dialogues from diasporic working class communities to create artworks that reflect upon historical development and its intimate effects on the lives of people. His focus is expressed through videos, photographs, and sculptures. The artist’s working method is driven by an ethical desire to transcend communication barriers with his community. This ethical desire is articulated through the use of humour and the creation of forms that complicate existing aesthetics that are vernacular to the sites and cultural practices of the artist’s community.

Luong has shown and screened artworks in places including the Images Festival (Toronto), Boers-Li Gallery (Beijing), Gudskul (Jakarta), and The Polygon Gallery (Vancouver). The artist has held research and resident artist appointments at the Inside-Out Art Museum (Beijing), HB Station Contemporary Art Research Center (Guangzhou), the Art Gallery of Ontario (Toronto), and Gallery TPW (Toronto). The artist’s works have been acquired and shown by The Rockefeller Foundation (New York City).

Accessibility: The gallery is wheelchair and walker accessible. If you have specific accessibility needs, please contact us at (604) 683-8326 or [email protected].

Centre A is situated on the unceded territories of the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh peoples. We honour, respect, and give thanks to our hosts.